All About Mastitis

The current thinking about mastitis has changed significantly in recent years, and the release of the new Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine protocol on the mastitis spectrum along with Dr Pamela Douglas’ papers on the inflammatory spectrum of the breast (one and two), has resulted in a complete shift in our understanding of the underlying causes, assessment and management of mastitis*.

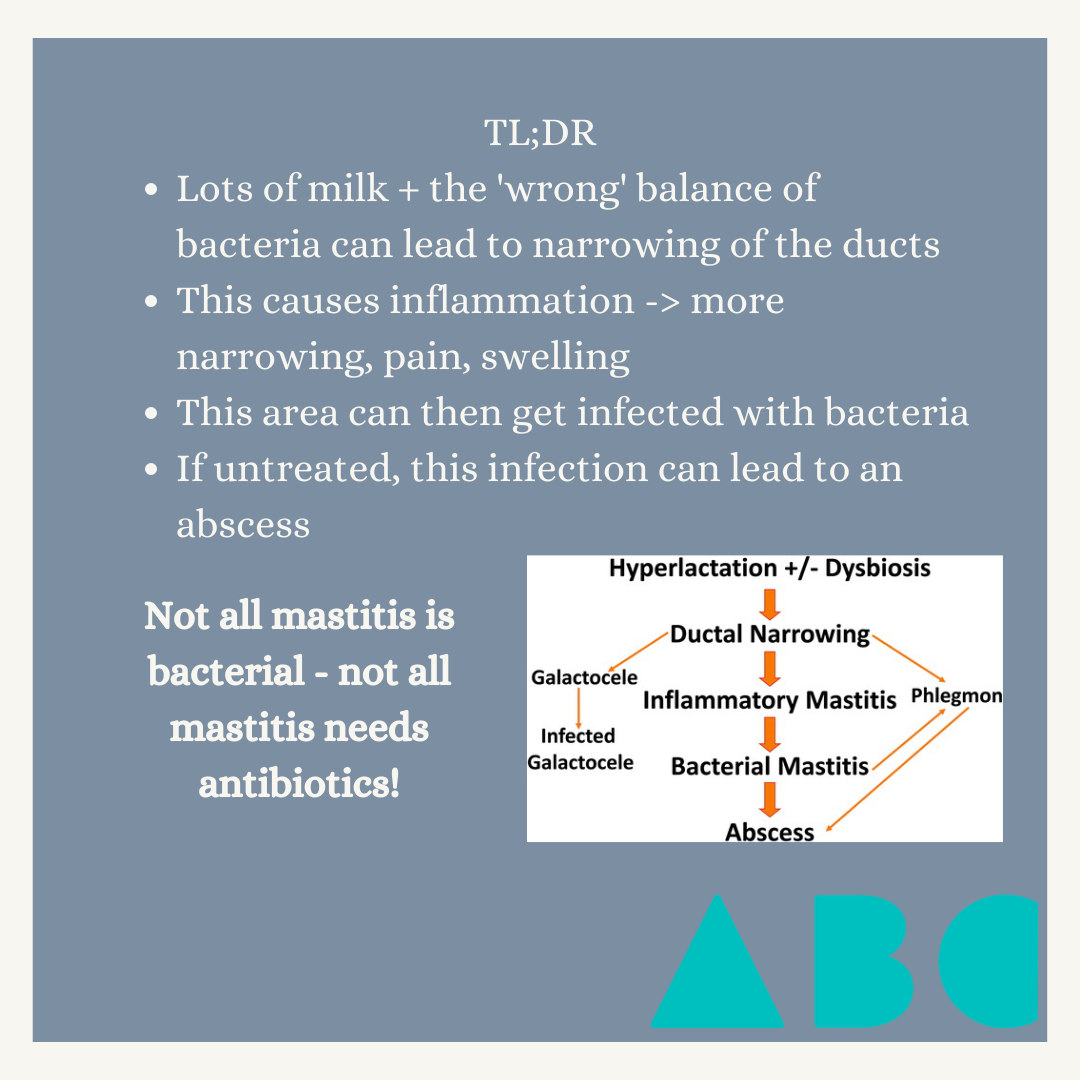

Once thought to be a purely bacterial entity that required antibiotics (and not much else) to treat, we now think of mastitis as a being on a spectrum, with microscopic damage to the lactocytes (breast cells) on one end, and breast abscess at the other.

Stretching of the ducts/alveoli = inflammation in breast & milk = more stretching = basement membrane/tight junction damage and rupture = stuff leaks out = heeaaaps of inflammation.

Here’s a summary of what we think happens:

Increased pressure within the ductal system leads to pressure being exerted on the tight junctions (bridges holding cells together) between the lactocytes in the alveolar units (the little cloud— or grape-like collections of cells where breastmilk is made)

This pressure in the ductal system can occur for many reasons, including engorgement/oedema, hyperlactation (producing significantly more milk than is required by your baby), milk stasis due to skipping feeds or inadequate removal of milk from the breast (eg if the baby is feeding poorly), underlying anatomical features including dead-end ducts, or previous surgery, and external compression from clothing/bras/binders/massage.

This increased pressure causes to mechanical changes to the cells, which results in the recruitment of the immune system to come and investigate - this can lead to pain and oedema (fluid in the breast tissue) which can worsen the ductal pressure.

If left untreated, this inflammatory response leads to an increase in the white blood cells in breastmilk as well as other inflammatory markers, as the immune system tries to investigate what the problem is.

“Applying this mechanobiological model of lactation-related breast inflammation, the key mechanism for the prevention or treatment of breast inflammation is avoidance of excessively high intra-alveolar an intra-ductal pressures”

Pam Douglas, Re-thinking benign inflammation of the lactation breast: a mechanobiological model

Principals of Prevention and Management

Frequent flexible milk removal

This is probably the biggest factor in prevention or management - offering the breast frequently and flexibly to your baby +/- expression if needed. Basically, as I usually say, “if in doubt, boob!”. Breastfeeds can be used for both nutritional, emotional, and sensory-motor nourishment so there is (almost) never a downside to offering the breast.

Most breastfeeding parents need to offer each breast about 12 times in a 24-hour period to maintain good milk production and good weight gain in their pēpi. These feeds may be long or very short, you don’t need them to have a “full feed”, and the timing between feeds can be hugely variable, sometimes as short as 10 minutes; the breast is never “empty”.

Fixing any underlying biomechanical issues - basically, this involves assessment and improvement of the fit and hold (or “latch” and “positioning”), which has the added benefit of reducing nipple discomfort, pain and damage, and unsettled infant behaviour at the breast (pulling away, arching their back, fussing etc). Nipple pain and super fussy infants is not normal and can usually be substantially improved with a good assessment (I’m biased, but I recommend someone trained in the Possum’s Gestalt breastfeeding method)

Avoid deep pressure on the breast - do not massage the breast, do not use vibration directly on the breast. This causes tissue damage and exacerbates underlying inflammation.

If you’re expressing milk, try gentle hand expression. If using an electric pump, ensure comfortable fitting flanges that are properly placed (ie aren’t “pulling” on the breasts)

Wean or downregulate milk production gradually

Suddenly weaning increases pain, inflammation and damage in the breast. If there is hyperlactation/”over-production”, milk production should be downregulated slowly, ideally with the guidance of a suitably trained lactation professional.

Avoid increasing milk production beyond an infant’s physiological need

This can happen when breastfeeding parents are told to try and “empty the breasts” to clear a blockage. Unfortunately this signals the breasts to make more milk, thereby increasing the pressure within the ducts and alveoli and can exacerbate the underlying problems

Gentle manual movement of breasts

Boob dancing! This comes from the idea that constant and irregular movement of the breasts helps with lymphatic drainage and downregulation of the inflammatory response.

This can also be done with very gentle lymphatic drainage/massage. This involved gentle stroking of the skin away from the nipple/towards the armpit. The pressure applied should be no more than you would use to stroke a cat or your newborns head. See here for a diagragm.

Another option is using the “breast gymnastics” technique developed by Maya Bolman.

Antibiotics should only be used if symptoms are severe and failing to resolve, and/or if there is a lactational abscess.

Treatment of Abscess

An abscess is a collection of milk and pus and other fluid containing immune cells, bacteria, and cell debris. Breast abscesses should be assessed with ultrasound, and treated with both antibiotics and incision & drainage. Sometimes a stent/drain will be left in place for 1-4 days after drainage to allow for healing, with this wound healing approximately 7 days after the procedure. This should not affect breastfeeding. Principals 1-5 above should also be applied.

*It’s worth noting that Drs Katrina Mitchell and Pam Douglas have opposing thoughts on the role of dysbiosis in the development of mastitis. In my summary of the ABM protocol, I focused on dysbiosis as this was prominent in the protocol but my understanding is that this is a theoretical entity and not currently backed up by research.